The Atomic Age, Reevaluated

On July 16, we celebrated—or, actually, failed to celebrate—the 79th anniversary of the beginning of the Atomic Age. Okay, a 79th birthday is not usually something to make a fuss about. However, I’m going to use this one to take stock of the Atomic Age—an age (the age?) in which all of us have lived for all or most of our lives.

I want to make some points—including one controversial point—about nuclear weapons: about the history of employing for potential military use the vast energy derived by splitting the nuclei of uranium or plutonium (fission)—or, subsequently, the even vaster energy produced by fusing hydrogen nuclei to form helium (fusion).

But first let me briefly commemorate the anniversary:

Scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, a top-secret U.S. effort to build an atomic bomb to help the Allies win World War II, figured out that a bomb made from an isotope of plutonium, plutonium-240, could work. But it would only work if those plutonium-240 nuclei could be made to split at the same instant.

That required an incredibly complex chorus of detonation explosions to “implode” the plutonium. The “implosion” trigger was designed based on calculations by smartest-human-ever candidate John von Neumann.

However, because of its complexity, this plutonium-implosion bomb, dubbed “Trinity,” needed to be tested. It was—in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

And it worked.

Man, did it work! It was awesome. It was terrifying.

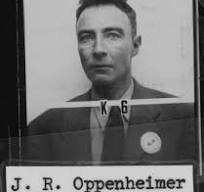

In an effort to describe what he felt that day, Robert Oppenheimer, the highly cultured scientist in charge of the Manhattan Project turned, as you’ll remember from the movie, to the Hindu holy text, the Bhagavad-Gita: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

That was, 79 years ago, the first atomic explosion ever on earth.

Two more soon followed: a uranium bomb dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, eventually killing somewhere between 90- and 140-thousand people, and a plutonium-implosion bomb dropped on Nagasaki three days later, which eventually killed between 60- and 80-thousand people.

World War II dutifully ended with the Japanese surrender on Sept. 2, 1945.

Here are some not-always-hugely-original points about the Atomic Age, which those explosions initiated. (Feel free to disagree in the comments.)

The final point is the really controversial one.

First point. While the case can be made that dropping the bomb on Hiroshima saved lives by forestalling a bloody invasion of Japan, it is much harder to make that case for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, whose only justification seems to have been a need to demonstrate to Japan’s leaders that the U.S. had more than one bomb.

Nagasaki bomb

Second point. Oppenheimer and some other scientists involved in the creation of the atomic bomb pleaded with political leaders in the United States and the United Kingdom to give control of all nuclear weapons to an international organization. Those political leaders were not persuaded.

But Oppenheimer was probably right. Because the result of not establishing some international ownership of atomic weapons was, initially, a nuclear-arms race: American efforts to prevent its post-war rival, the Soviet Union, from obtaining the “secret” of the atom bomb and then the hydrogen bomb failed. And the two countries fell into a terrifying competition to build the most and the most powerful of these weapons of mass destruction.

The other result was ongoing nuclear proliferation: so far nine countries possess nuclear weapons: Russia, the United States, China, France, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Israel and North Korea (oy). Iran (oy, vey) may be next.

Third point. Nuclear weapons, in giving humans a means to wipe out much of the population of the earth, presented humans with a large, new worry: the existential fear that malevolence or even a misread radar screen could cause some trigger-happy world leader or general somewhere to press the figurative button causing a counterpart elsewhere to press a similar button and soon: poof, or as Tom Lehrer sang in 1959

We’ll all go together when we go,

Every Hottentot and every Eskimo.

When the air becomes uraneous

We will all go simultaneous….

President John F. Kennedy and United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson during the Cuban missile crisis.

Such worries were heightened by particularly intense geopolitical conflicts, such as the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. The construction of “fallout shelters” and the implementation of “duck and cover” drills in schools, in anticipation of possible atomic attacks, amplified such fears.

A 1960s fallout shelter.

Fourth and most controversial point: Nonetheless, the case can be made that atomic weapons have—so far, at least—made a positive contribution to world peace by making war between major powers seem unimaginably horrific.

Is this not a possible explanation for the fact that the United States, the Soviet Union/Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China—have all avoided firing upon each other’s troops for the 71 years since the end of the Korean War? If the possibility of inciting a nuclear conflict had not been there, might the Soviet Union have sent troops to Vietnam or might the United States, more recently, have sent troops to Ukraine?

This is what the Strangelovian hawks called “deterrence.”

Basically, with those last two points, I’m suggesting that we try—in an act of mental fission—to hold two contradictory ideas in our heads at the same time:

First idea: Atomic weapons have scared the shit out of humankind for more than three-quarters of a century by creating a mechanism by which we ourselves could destroy ourselves. We, in other words, could have “become death” and maybe still could “become death.”

Second idea: But atomic weapons have, so far, seemed to keep humankind’s most powerful nations—who in various alignments had fought two huge wars in the previous decades—from again going to war with each other.

My father enlisted during World War II and ended up interviewing, for the Army newspaper, the pilot of the plane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima a few days after they dropped it. My dad and I (an optimist, even then) used to argue about whether there would be another world war. I’ve been right, so far.

So, happy 79th birthday to our contemporary, the Atomic Age. Perhaps you did accomplish something that has, so far, proven—kind of, sort of, in some way—positive after all.