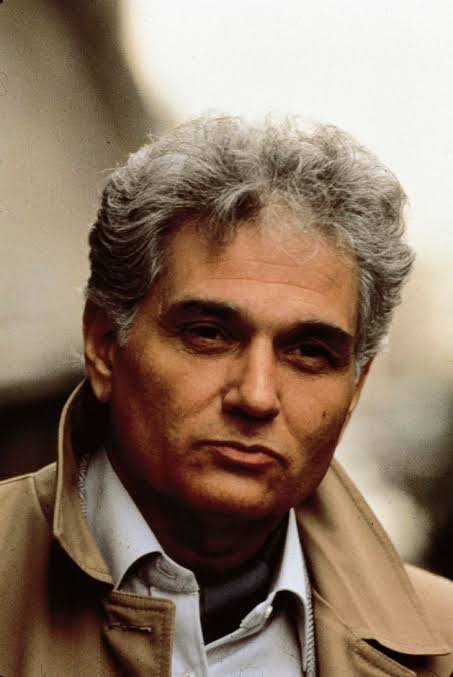

Bob Dylan A-Changin’

Earlier installments in our series on the Roots of the Hippie Idea:

Click for the introduction to this series: “The Roots of the Hippie Idea.”

Click for “Whitman and Thoreau and the Hippies.”

Click for the Beatniks and the Hippies

Click for Modernism and the Hippies

We were born into this—this notion that to be an artist was perpetually to be rethinking what an artist should be, a notion very much at the heart of James Mangold’s Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown.

I don’t think Mozart saw himself as involved in continually reinventing music. Rembrandt was struggling to portray what he saw, not struggling to reconceptualize what painting might be.

But the rules of painting had changed dramatically in Paris in the second half of the 19th century as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro began painting en plein air; painting fast, with a palette of bright, sunlit colors; and painting ordinary people—not Napoleon on his horse. A theory—a wonderfully invigorating theory—had been placed before Napoleon’s horse.

And, of course, impressionism was arriving at the same time as politics and economics were also gaining a couple of even more ambitious isms.

Impressionism lost its excitement for artists (though not for their audiences) in the 20th century. But what did last for most of that new century was this notion that to be an artist was to rethink the rules of art itself. So, we had Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism and Postmodernism.

Jazz went through, among other fashions, big band, swing and bebop.

Even philosophy underwent periodic reconceptualization in the 20th century: phenomenology, existentialism, analytic philosophy, ordinary language, logical positivism, structuralism, poststructuralism and deconstruction.

It was all acutely self-conscious, somewhat precious, inescapably meta and kinda fun—you did not just get to paint or play jazz or do philosophy; you got to theorize about what these endeavors should be.

Cool.

Which brings us to Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival on the evening of July 25, 1965. Dylan’s decision to infuriate the sainted Pete Seeger by bringing a full electric band onto the folk festival stage with him was, as a bunch of 20th-century philosophic schools might put it, “overdetermined.”

Robert Zimmerman grew up in Hibbing, Minnesota, at the northern end of that great blues road: Highway 61. Zimmerman had played Little Richard songs in a loud high-school rock band before reincarnating: as a Woody Guthrie-style, vagabond folkie with a literary-sounding last name. The first electric song Dylan played at Newport that night, “Maggie’s Farm,” had appeared, a few months earlier, on an album Dylan entitled, Bringing It All Back Home.

And Dylan was an inveterate shape shifter—though in 1965 we hadn’t yet seen enough of the shapes he was to adopt to realize that.

We also didn’t realize then the extent to which Dylan chaffed under any efforts to preserve him in a shape he felt he had outgrown.

And what exactly was the nature of Dylan’s rebellion at Newport in 1965? As shown in Mangold’s movie, which is quite good at setting the scene, if not at exploring the ideas bubbling up in that scene, Dylan went on stage with a drummer, an electric bass player and a couple of electric guitars.

The previous summer Dylan had notably turned all four Beatles on to marijuana, while they were visiting New York. And in the summer of 1964 at Newport Dylan had sung perhaps the most powerful ode to hallucinogenic drugs ever written: Mr. Tambourine Man:

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky

With one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea

Circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate

Driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow.

Remarkably, no one complained about the drug stuff. But drums and electric instruments! Heaven forfend!

Bob Dylan would soon reveal himself to be something of a leavin’-it-all-behind addict. And perpetually moving on to the next thing without looking back actually kind of worked in lightly anchored, newness-prizing art forms like 20th century painting and second-half-of-the-20th-century rock ‘n’ roll.

Picasso had had his Blue Period, then his Rose Period, before helping launch Cubism. Dylan—never one to be out-morphed—followed the masterful rock ‘n’ roll albums, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, by stripping away the electric guitars and flights of beatnik poesy for John Wesley Harding in December 1967, then making a country album, Nashville Skyline, in the spring of 1969.

And we all—our generation, even the Beatles themselves—were taking lessons from the peripatetic Mr. Dylan on the great power of genre, of style, of reinvention. For Dylan never took genres lightly. For him it was always whole hog—until it was nothing, and he had moved on.

Which made Dylan—though perhaps the most interesting character in rock ‘n’ roll—an odd choice as a role model. Following him into something was okay, but it always necessitated following him out of the something we had previously followed him into.

Maybe we could handle that: Country music, sure! Far out! But then it reached the point where we could no longer handle it.

For in 1979, Bob Dylan reappeared in the one guise that was probably the most difficult for most members of his previously loyal audience to abide: as a born-again Christian, baptized in Pat Boone’s pool. (Though the first Christian record, Slow Train Coming, released in the summer of 1979, was actually pretty good.)

So what was the lesson of all these modernist shifts, often into pre-modern roles; shifts we first noticed at Newport in 1965? What was Dylan teaching—what had Picasso and, maybe, Jean-Luc Godard who had gone before, and those, like John Lennon, who followed, been teaching? It sure seemed like these restless souls were saying: Keep a-changin’. Don’t look back. Be true to your feelings in the moment.

However, we were not—most of us—brave enough for that, for picking up and leaving it all behind. We were not—most of us—even true artists. We were, instead, wise enough to stop practicing guitar-fingerings in mom and dad’s basement and, eventually apply to law school. Shape-shifting did not work all that well with spouses and kids and careers.

Nonetheless, our inner Bob Dylans were never entirely abandoned. You could honor them with your broad and shifting tastes in music, with the odd books you read, the art-house films you caught, the dope you smoked on weekends.

There remained a little hippie, a little artist, a little a-changing, a little Bob Dylan, in us all.